En català | En castellano

“There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Galatians 3:28)

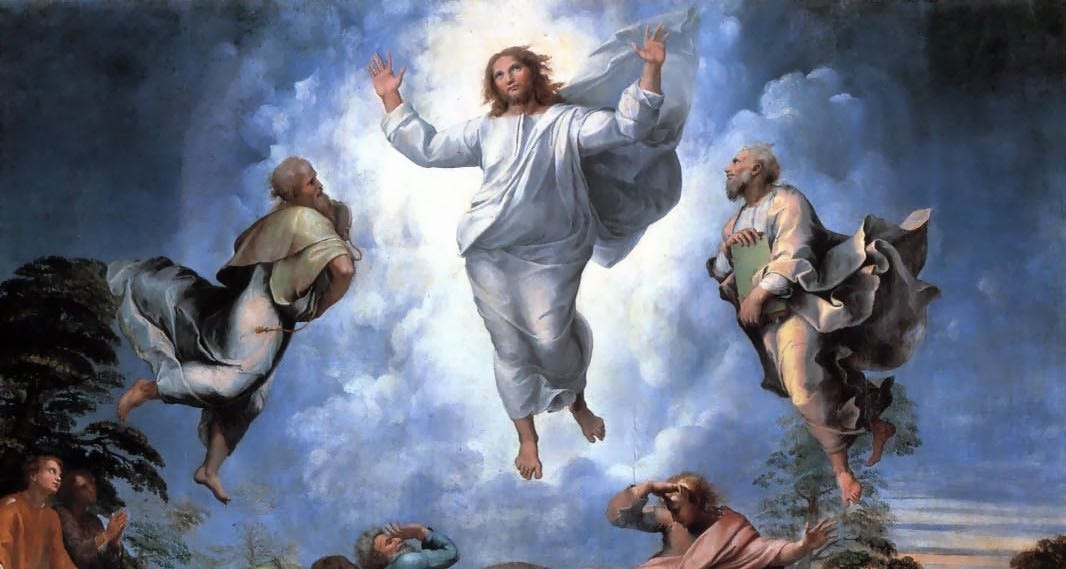

In millions of Christian churches worldwide, the scene of an execution engages visitors with a profound spiritual experience. The figure of a man on a cross is displayed as a powerful symbol of the sacrifice made by the son of God for the redemption of humanity’s sins. The story of Jesus is universal, shared among people of all backgrounds who travel the path of faith on their way to salvation. A small placard nailed to the cross is the only element that connects a timeless representation to the actual man who was executed nearly two thousand years ago. It contains a revealing inscription: “INRI”, the Latin initials for “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”. Despite his transcending influence, the life of the historical Jesus remains shrouded in mystery: was he driven by political motivations, as suggested by the designation “King”? What was the reason for his execution? The man behind the myth is hidden by a veil of religious allegories, a nebulous historical record, and the foundational circumstances of the cult he created.

Jesus lived during a politically agitated time that was crucial for the fate of Israel. One hundred and thirty years before his birth, a Jewish rebellion against Greek rule had established an independent kingdom after centuries of exile and foreign control. This achievement, still celebrated by Jews today during the festival of Hanukkah, was soon threatened by the rising power of the Roman Empire. The historical period surrounding Jesus’ life, extensively documented by 1st-century historian Flavius Josephus, was marked by the struggles of the Jews to maintain their independence. Numerous revolts against Roman domination resulted in ultimate defeat in the early 2nd century CE, and a Jewish state was not to reemerge in the Levant until the creation of modern Israel in the 20th century.

In addition to the inscription on the cross, there are several indications that Jesus was not removed from the political turmoil of his time. His title, “Christ,” is the Greek translation of the Hebrew word “Messiah” (meaning “anointed”); a term that has significant political implications in the Hebrew Bible, as it designates the ruler of a united Israel under God. Jesus was given a Roman punishment typically reserved for individuals engaging in subversive behavior, such as the slave leader Spartacus and his fellow combatants or several Jewish rebels mentioned in Josephus’ chronicles. According to the four canonical Gospels, the fate of Jesus was tied to that of a political prisoner, Barabbas, a man “who had been thrown into prison for an insurrection made in the city, and for murder” (Luke 23:19). When the Jewish crowd chose for Barabbas to be pardoned over Jesus, the Son of God was crucified between two members of the rebel band. If Barabbas, not Christ, was truly the ringleader of the insurrection, the royal treatment in the inscription INRI would seem more fitting for him than for the man who was crucified. In comparison to someone like Barabbas, how could Jesus represent such a threat for both Romans and Jews? The history of how Christianity developed after Jesus’ crucifixion holds illuminating insights into these apparent contradictions.

The case for the existence of Jesus

“About this time there lived Jesus, a wise man, if indeed one ought to call him a man” (Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.63)

The question of the historical Jesus is complex because there are no documents written during his lifetime that attest to his existence. Jesus was crucified around 33 CE, but the first non-Christian reference to him (a brief and controversial fragment in one of Josephus’ books) does not appear until 93 CE. The Gospels, which relate the story of Jesus’ life, are believed by historians to have been written between 70 and 100 CE. Their focus is on Jesus’ miracles and teachings, and their metaphorical style makes it difficult to discern the historical figure behind the narrative. The parallels in the story to other ancient divinities and the scarcity of early sources have led some scholars to posit that Jesus may not have existed as a historical person, but rather as a mythological figure created by early Christians. This perspective, known as mythicism, is far from widely accepted among historians, but has gained attention and support in recent years.

The earliest written references to Jesus that have survived to the present day are the letters of Paul the Apostle, written in Greek like the rest of the New Testament and sent to various incipient Christian communities around the Mediterranean. In his Epistle to the Galatians (54 CE), Paul laid the foundations of Christian doctrine that remain in place today. He introduced the notion of faith in Christ as a means to escape the constraints of the Law of Moses, extending the cult of the Jewish God to non-Jews and effectively making the new religion universal. Despite not being one of Jesus’ twelve closest disciples, Paul called himself an apostle and was a major figure in early Christianity. His missionary travels were instrumental for the spread of the new religion, and his writings made him one of the most influential thinkers of all time.

Paul’s letters contain surprisingly little information about Jesus’ life: There is not a single reference to his childhood, Mary and Joseph, or Nazareth. Nothing on Pontius Pilate, Barabbas, or the appearance before the Sanhedrin. The first person to leave a written testimony about Jesus did not seem to know a lot about the main character in his works. While this point is one of the pillars of the mythicist thesis, there are two key arguments that strongly suggest that Jesus did in fact exist. The first is the robust historical evidence supporting the crucifixion event: in addition to being a central topic in Paul’s writings, it is mentioned in several independent sources, making it hard to claim that it would be based on a fabricated fact. The second one is that Jesus had a brother whose name was James and who played an important role in the Church of Jerusalem following Jesus’ death. James appears in the Gospels, in the Acts of the Apostles, in Paul’s letters, and also in Josephus’ historical record. The fact that Jesus had a sibling challenges the notion of Mary’s perpetual virginity, so the Church has traditionally argued that he was not an actual brother, but rather a cousin or a stepbrother, even if the Greek word used in every text (adelphos) unequivocally means brother. He was not referred to as brother in the sense of comrade, because some of the men who were closest to Jesus, including Peter and the other apostles, did not receive that designation. Paul described meeting James during one of his trips to Jerusalem: “I went up to Jerusalem to get acquainted with Cephas [referring to Peter] and stayed with him fifteen days. I saw none of the other apostles – only James, the Lord’s brother” (Galatians 1:18-19). If James was a real person, his brother Jesus must have been real, too.

Paul vs James: A conflict between Greek and Jewish Christianity

“I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting the one who called you to live in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel - which is really no gospel at all. Evidently some people are throwing you into confusion and are trying to pervert the gospel of Christ” (Galatians 1:6-7)

The way the life of Jesus was portrayed in the New Testament was defined by the outcome of a fundamental conflict that took place within early Christianity. Paul and James were at the helm of two bitterly opposed factions among Jesus’ followers: James, on the one hand, asserted that the principles of the law of Moses must be kept. In his view, the cult of Christ had to be restricted to Jews. Like Jesus, James’ native language was Aramaic. Paul, on the other hand, advocated for the Christian creed to be opened to Gentiles, people who were not bound to follow the Jewish Law. He was a Roman citizen, born into a family of diaspora Jews living in Tarsus, in modern-day Turkey, and he wrote in Greek. An important focus of Paul’s writings was dedicated to defending his views over those of his rivals, whom he called “Judaizers”. His revolutionary idea to break with Hebrew tradition and distance the new cult from Jewish practices, in particular circumcision, was not well received in the Jerusalem community. In one of his trips to the Judean capital, Paul was arrested after being confronted by James and his followers: “The next day Paul and the rest of us went to see James, and all the elders were present. […] They said to Paul: ‘You see, brother, how many thousands of Jews have believed, and all of them are zealous for the law. They have been informed that you teach all the Jews who live among the Gentiles to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs.’” (Acts 21:20-21).

The religion spread by Paul initially took hold in cities with a large presence of Hellenized Jews, Jews who like Paul had adopted Greek as their first language and had grown culturally apart from their co-religionists in Israel. Paul’s missionary trips around the Mediterranean were a resounding success and the Christian community grew exponentially by adding members from various religious backgrounds. Christians that continued to adhere to Jewish Law, on the other hand, were severely weakened after the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-73 CE. After the Roman army put Jerusalem under siege and eventually destroyed the Jewish Temple (of which only the Western Wall still stands today), Jewish Christians formerly led by James dispersed across the Levant. The existence of Jewish Christian communities such as the Nazarenes and the Ebionites is documented up to the 7th century, but their importance gradually faded and was eclipsed by Gentile Christianity. The entire body of literature of early Christianity is written in Greek and none of the original Jewish Christian texts, presumably written in Aramaic or Hebrew, have survived to our day.

The theological victory of Paul’s followers over James’ followers and the creation of an entirely new religion rather than a new sect within Judaism meant that Gentile Christians got to tell the story of Jesus’ life and teachings in their own terms. But the original Jesus, the man who died on the cross, surely had more in common with his brother than with Paul, a man he never met and who persecuted Christians before converting on the road to Damascus. The designation “Christ” was probably given posthumously, as Jesus is unlikely to have used a Greek title as an Aramaic-speaking Jew who spent most of his life in the land of Israel. Based on his brother’s stance, the inscription on the cross, and the Roman punishment he received, Jesus was probably a pious Jew who potentially opposed the occupation of his nation by the Romans. As historian and archeologist Robert Eisenman points out in his book James, the brother of Jesus: “Who and whatever James was, so was Jesus”. Paul himself acknowledged that the Jesus he described might have been very different from the Jesus described by Judaizers: “For if someone comes to you and preaches a Jesus other than the Jesus we preached, or if you receive a different spirit from the Spirit you received, or a different gospel from the one you accepted, you put up with it easily enough” (2 Corinthians 11:4).

Jesus Barabbas, the insurrectionist

“We have found this man subverting our nation. He opposes payment of taxes to Caesar and claims to be Messiah, a king” (Luke 23:2)

In his Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, 3rd-century biblical scholar Origen of Alexandria devoted significant attention to the following quote: “Pilate said to them, ‘Whom do you want that I release to you? Jesus Barabbas, or Jesus who is called Christ?’” (Matthew 27:17). For the modern reader, this passage holds a surprising revelation: in the source text that Origen was using, both Barabbas and Christ were named “Jesus”. Origen found it implausible for a criminal to have the same name as the Messiah and thus favored simplifying it to just “Barabbas”. Most later copies and modern translations of the New Testament adopted this variation, even if it may have represented a deviation from Matthew’s original text. But what Origen (writing in Greek) did not mention was that Barabbas also held a significant title: in Aramaic, Barabbas means “Son of the Father”. It is a patronymic surname – a commonly used form in Semitic languages - where bar means “son” (similar to ben in Hebrew, or bin in Arabic), and abba means “father” (abba in Hebrew, ab in Arabic). So in the original Gospel of Matthew, the man who narrowly escaped crucifixion shares not only his first name with the man who took his spot on the cross, but also the same designation: Jesus Christ himself is referred to as the “Son of the Father” in the Bible, only using the Greek term instead of the Aramaic one.

The story of Jesus Barabbas is much more aligned with the historical context than that of Jesus Christ: the story of a Jewish insurrectionist who was sentenced to death by the Romans for leading a rebellion, a man who proclaimed himself king of the Jews (INRI), the Aramaic Messiah, the brother of James, who fought to uphold the Jewish Law. It is possible that the historical Jesus was none other than Barabbas, whose death on the cross with two of his accomplices inspired the start of a new cult within Judaism. The figure of Christ as it is reflected in scripture - the Greek Messiah, the apolitical miracle worker and teacher, the timeless deity - might have emerged later as Paul and his followers distanced themselves from James, Judaism and the original Jesus. The narrative of a Jewish patriotic leader was at odds with a message constructed around salvation for all humanity, so Paul may have deliberately avoided the subject of Jesus’ political motivations and chosen to focus on the topics of crucifixion and resurrection. By the time the Gospels were written, decades after the events in question, Paul’s “other Jesus” might have become so different from the historical person that Jesus Christ and Jesus Barabbas were presented as two different people, each of them implicitly associated with a different branch of the nascent religion.

Some modern Bible scholars such as Bart Ehrman question the historicity of Barabbas: the Roman custom of releasing a prisoner in honor of the Passover festival is not documented anywhere outside the New Testament, and in all other instances Pilate proved to be ruthless against anyone who challenged Roman authority. According to this view, the Gospel representation would have been conceived with the purpose of shifting the blame for Jesus’ execution from the Romans to the Jews. This premise can also be used to conclude, however, that from the two men in the scene it is actually Barabbas who reflects the historical Jesus, whereas the allegorical figure of Christ would have been introduced later in a way that could not be associated with the original Jewish insurgent.

The search for the true nature of Jesus has captivated Christians and non-Christians alike for nearly two thousand years. Centuries of theological debate, centered around Jesus’ divinity and the meaning of his teachings, have shaped Christianity and its different denominations, leading to divisions and even war. A more empirical approach has been limited by gaps in the historical record, such that every hypothesis inevitably contains an element of speculation. What does clearly emerge from the Bible’s inconsistencies, however, is that some of the most relevant dogmas in Christianity, such as its universal character and the primacy of faith, were forged in the context of a religious confrontation after Jesus’ death. There are clear omissions in the New Testament around Jesus’ political standing at a time of struggle, but there is also an indelible fingerprint of a Jewish man who was executed by the Romans for claiming to be king. Jesus the man certainly existed, but he is also the personification of a revolutionary concept, “God is salvation,” which perhaps not coincidentally is the etymological meaning of the name “Jesus” in Hebrew. Was Jesus a rebel leader, an apocalyptic prophet, or was he a mythological figure? He might just have been all three.

Hola Jordi, molt interessant l’article. Jo també penso que Jesus va ser un líder de la revolta político-social mes que un líder religiós. I també crec que el creador del cristianisme com areligió va ser Sant Pau. M’agradaria saber la teva opinióp sobre la figura de Joan el baptista. Congrats for your blog!!!

Very interesting and well written! Thanks 🙏